If I asked you why Photoshop has such deep foundations in numbers, what would you answer? Probably the usual, bits, ones and zeros. Sure, our migrations from an analogue system to a digital one forced us to redefine how we measure quantities, and identify qualities. But it is also true that in many fields this is hidden to the final user, while in Photoshop we continuously measure numbers, use curves, do calculations (sometimes literally).

While in the process of learning Photoshop it is crystal clear that there are many elements that is impossible to divide from math. While we are uneducated and until a certain point we could have used numbers only as vague reference, a part of a clunky user interface, and curves as a visual cue. Even blend modes could be just used by comparing aesthetics, and experience, leveraging our visual system (darker, brighter). But sooner or later we will face that point, and we’ll be forced to make a decision.

Color and math

Often that border is Apply Image. From an educational point of view that tool often goes with a great will to improve own skills, and to try doing things differently. There is a great deal of amount of very useful and very out of fashion tools in Photoshop, that just aren’t for novices, nor to be found in tutorials. This is fertile ground for the first math operator we will learn about, Apply Image will be perceived as sum, coincidentally the first operator we learn as children.

Apply Image allows us to add an element where we want, when there was empty space, or another element. Likewise, a mask is a subtraction. Multiply and difference are both blend modes. From here on we will find countless references, parallels. Probably more than we wanted to. This lonesome trip, is why Photoshop is a great and poor software, at the same time.

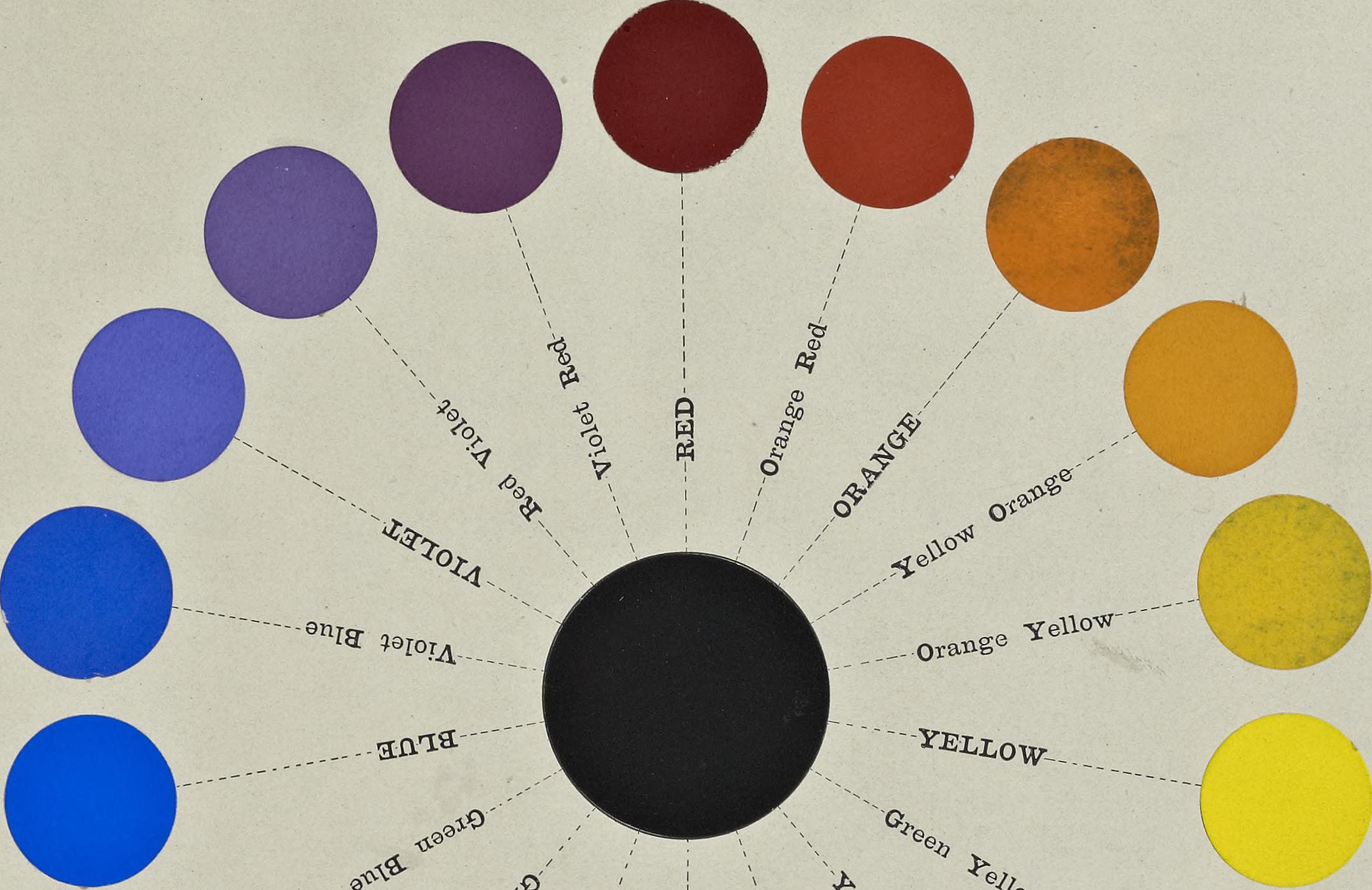

Immage from “A class-book of color : including color definitions, color scaling, and the harmony of colors”, 1895

Advantages of a mathematical system

At first it may seems that other applications and softwares that only use aesthetics may be more usable and faster. But leveraging math allows us to use some impressive features. First, we can talk about an education in digital color, that is more of a discipline, more democratic. We can have a common language, a philological system, a scientific approach (if we want to). Everyone can approach color correction, and the most challenging post-production nightmares, because these don’t require visual perception experience, nor they request a deep understanding in the digital processes (well, not always). This is not true in prepress, for example.

Truth is, even if we dislike this approach, it is knowledge we can reach, easily. Adding, or removing, yellow (I want this yellow-er here) is something we can easily understand, even if we fail to define saturation. Some of us, with a scientific background will be facilitated, and watching a curve will not need an explanation when reading input and output.

Some others will need more time, smaller steps, but my experience says that there’s risks they will learn even more. This is also the very reason for many photographer struggling with color correction, and to try often to infuse a creative aura to a process that should be mostly objective and that has its own ethic rules.

One day Seth Godin, a marketing genius from New You City told that ”Four of us visited a fancy restaurant on Saturday. Imagine our geeky surprise when they brought out a Microsoft tablet instead of a wine list. … What's bad is that the person who's going to spend $100 or $1,000 on a bottle of wine isn't a hyper-rational geek in search of the optimum solution (hint: we bought the cheap stuff but it was still 5x the cost of of the wine in a store). Instead, we're looking for a buying experience (courting the sommelier, sniffing the cork) that adds a huge percentage of the value to the purchase.”

I do feel sympathetic to this issue, while thirsty for more power in the post-production workflows we underplayed an entire system that had its noble rules and history.

Math and photography

I always stated that being a photographer doesn’t means to stay in front of a computer, although I also think it makes us better at it. There is quite the amount of math in photography as well, of course, but what is the reason we switched to digital in the first place? We were aiming to a faster workflow, flexibility, being ready for the web. Right?

An equation that has many variables. Now my photos are ready faster, no one has to work on them, or is involved in any part of the process. I’m the only responsible for the results, and I can do pretty much whatever I want. Now for the tradeoffs, first we struggled for years with dynamic range, and colors. Second the amount of time we now have to invest to learn, understand, research and practice is massive. Learning color correction refines our photographic skills, but learning digital so much don’t. A boring couch photo will be a bad shot whatever the quality of our post-production.

What Photoshop does is to compile an image in elements that a machine can handle, numbers, channels. But this is only the beginning, Photoshop Team’s engineers and developers could have hid numbers like it happens in other applications. Trying to develop a user interface more like Lightroom, for example. Instead Photoshop allows users to meddle with images deep architecture, to empower colorists with the highest form of control. And so my question now is: can we even envision a radically different workflow in Photoshop that doesn’t include numbers at all? Is it even possible to achieve a quantitative and qualitative analysis without numbers? Let’s evaluate alternatives.

Alternative systems

What could we use to edit our images? Let’s first identify our goal: producing better images. We could try build this new system not on numbers but on aesthetics, trying to replicate the objects in our pictures to their best version there is. We could build a database of models, the best walls, the most beautiful flowers, the ripest fruits. But this approach will not consider how our visual system actually works. A wall can be in the shadow, a field can be set in a rainy landscape, and an apple portrait in mixed lighting conditions. And it is important to note that I’m intentionally talking about objects. With skin tones this will be simply impossible, as chromatic variations in such a small range is infinite, and so are exceptions. And this chromatic variations is essential to skin tones aesthetics.

No, aesthetics is not our ally. But maybe, instead of a centralised aesthetical system, we could use one focused on a single user, entrusting the single colorist with what, and how much, to improve. Actually systems like this existed for years, a notable one was built by Nik Software engineers (later bought by Nikon, and then Google) for Nikon Capture NX and Viveza. No numbers, no channels (or at lest not to be seen by the user). Everything is decided by the user (to me a colorist no more) on a personal basis. Of course saturation, luminosity and contrast are the same concepts, and we still have slider where we can match values with results, what changes dramatically is how we handle them. Now we have “control points” that can select part of the image, in a mix of radial and colour-based fashion.

Aesthetic VS math

Is this approach efficient, is it working? I do not think so. It has severe tradeoffs. Let’s take a look at the most important. First micro-adjustments. A curve in RGB that results in a change of one or two values in the A and B channels is a common move in Photoshop, maybe pursuing neutrality. But when I do this what I’m looking for? Am I looking for the image to see when I achieved neutrality? No, I’m looking at numbers in the info palette, the only precise, effective, way to be sure of colors, eventually I look the image as well, mostly to see if I’m ruining other elements.

I know I’m working on something so trivial not because it makes the image so much better, but because I’m looking for a certain value. As soon as I remove numbers from the process what happens? Control points do not shows precise feedback of what is going on, eyes are my only reference, so I need to see a change to evaluate it. Fine tuning is impossible.

Also, when working with blends in Photoshop we edit the images on a full-frame basis, even when we mask. This means we rarely divide or split the image. On average we can say that our results will be more natural, especially on transitions.

Math and workflows

We would have, actually, a ton of issues even only trying to build a workflow with no numbers. Issues regarding color management, issues in collaborative environments, issues that color correction can brilliantly avoid exactly because it has a numeric foundation. A certain number, in a certain file will be exactly that number in every computer in the world.

If we deprive our post-production models of aesthetics what is left if not just pure objectivity? Is there, then, a way to manipulate this raw objectivity that doesn’t contemplate numbers? The answer to this question is why Photoshop, and this is my opinion, is still, and forever will be, deeply connected with a math system that will always empower users to access the most intimate structures of any image. Unlike many other applications.

And let’s hope no-one will ever take this away from us!